The Manchurian Candidate (1962)

You know, sometimes I watch a film and find myself with a surplus of things to say, especially when I’m fairly negative on something or find another something especially strong. However, there are lots of times when I watch a film, find myself enjoying it quite a bit, and yet have little to no idea of what exactly to say about it when it comes time to put the pencil to the paper. And then there are films like The Manchurian Candidate where I honestly have no earthly idea how I even feel about the movie, much less how to describe it to others or whether or not to recommend it.

You see, this film is usually considered a taut, bleak thriller with a chip on its shoulder regarding the Joseph McCarthys of the world, but to my modern sensibilities, I can’t help but feel that it resembles a surrealist film more than anything. In one legendarily bizarre scene after another, the film manages to keep topping itself until the ultra-bleak ending sends you out with a bang: dazed, confused, and unsure of what the hell you just experienced.

False idols

But let’s back up. The plot of this film is well-known at this point and oft-referenced: a group of soldiers led by Sergeant Raymond Shaw are captured during the Korean War and taken to a communist POW camp, whereupon the sergeant is brainwashed into becoming a sleeper agent for a communist conspiracy bent on infiltrating the United States. Raymond won’t even know the awful things he’s doing in their name, as he's under hypnosis, and thus shouldn’t be likely to give himself away.

Afterward, he and his squad are handed back to the Americans with a phony implanted memory of them leading a triumphant escape from the camp. Everyone is treated like a hero when they come back home, and things seem cheery… at least until a number of the men under Raymond’s command begin to have strange dreams where they witness Raymond murdering two of their friends while under hypnosis: the two men in their squad who didn’t make it back home, in fact. This especially bugs Major Marco, who begins to slowly become suspicious that something about their heroics during the war just doesn’t sit quite right. Now it’s a race against the clock: can Marco uncover the conspiracy fast enough to keep Raymond from being activated and used by his mysterious American handlers?

Hitchcock. Lynch. Hideaki Anno.

See, doesn’t seem all that bizarre right? Sounds like a perfectly enjoyable little political thriller, one which is an obvious product of an era suffused with "red" paranoia. Acclaimed filmmaker John Frankenheimer directs in one of his first such jobs, and hey, it stars Frank Sinatra! So why exactly does this film feel so totally mystifying to me?

Well, what if I told you that the sleeper agent Raymond Shaw has serious mommy issues? You see, he’s a big ole’ momma’s boy who not only still lives with her well into his adulthood, but who won’t shut up about her any time he’s out with male pals or potential female lovers. He holds a grudge against his braindead stepfather Senator Iselin (a clear stand-in for McCarthy himself) insisting with his every other line that the dude is not his father, and generally just comes across as a total loser, especially when he’s dressed up in a child’s cowboy costume in one of many bizarre scenes towards the middle of the film. Needless to say, when I pictured the film’s pitiful antagonist, forced to murder against his will without feeling, I didn’t picture Rupert Pupkin. This is without getting into the fact that Raymond’s mother is herself an extremely important character, whom the majority of the plot revolves around. Is that not kind of strange? Maybe it’s just me.

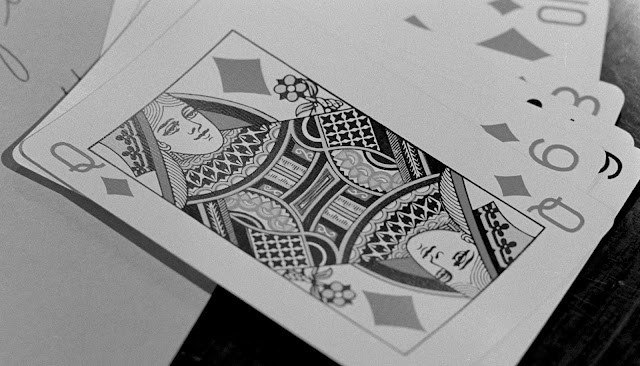

But that’s just the beginning of the weirdness. One of the film’s first scenes, where we see Raymond’s programming demonstrated for us, is really well done and clearly intentionally surreal. We see the scene playing out from a rapidly changing blend of harsh reality and the projected images that the hypnotized American soldiers are seeing in their heads as the whole thing plays out. It's positively teeming with black comedy, as the situation is inherently absurd until it leads to the violent execution of two of the soldiers, with none of the others batting an eye. Perhaps this should have prepared me for a strange viewing experience, but for one reason or another, it did not.

Exhibit A: the infamous “train scene." We’re introduced to Major Marco, clearly suffering from PTSD, attempting to light a cigarette on a boxcar, sitting next to Janet Leigh. After a number of failed attempts where the flame is blown out just as it reaches the tip of his cigarette, Marco suddenly stands up and flees the room to get some fresh air. Of course, Janet Leigh can’t help herself and decides to go check on him, and what follows is probably the single strangest conversation in cinema.

It has to be intentional, or at least that's what I keep telling myself. It has to be a clue of some sort. There simply must be some kind of detail that I’m missing, right? Why else would it seem like Leigh is speaking in spy code? Why else would she continue to repeat her phone number and address out of context every other line? Could it be nothing more than a simple case of the film's male writers not understanding women, believing it entirely realistic that Leigh drops everything in her life to become Marco’s lover after speaking to him cryptically for a few minutes, or could the film be implying she’s some kind of spy herself? It’s reasonable to assume that, like many previous scenes in the film, this bizarre exchange on the train would end by smashing to Marco sitting up in his bed in a cold sweat, but no: it’s apparently real, made all the more clear when this character shows up again later and… get this, does nothing the whole rest of the film while continuing to speak in riddles. The only explanation that I can see is either the spy one or that Marco is only imagining her as a result of his trauma, and neither of those really puts the issue to rest entirely.

But that’s not all. There’s a scene closer to the middle of the film where Raymond reminisces about a woman he once loved, and I kept thinking this was going to be revealed to be an implanted memory later on because, well, the flashbacks are just so absurd! We practically see him, the woman (whom he meets and proposes to in the span of maybe a half hour,) and her father holding hands and dancing a jig at the dinner table, laughing uproariously over nothing to the point that it genuinely becomes creepy. And then, just when you think the scene will give itself away as some kind of trickery, it transitions to another bizarre scene and nothing more is ever said about it. When taken with the extended “costume ball” sequence where everybody looks about four years old, I’m one hundred percent sure that both Richard Condon and the screenwriter adapting his novel had to be trying to convey something to us, but what exactly is anyone’s guess.

So damn lovable

I think the reason that this bizarreness doesn’t quite translate into greatness to me is that so many other aspects of the story aggravate me, not the least of which are the caricatures that populate it. We’ve already discussed Raymond and his idiotic, strawman stepfather. There’s of course his mother, who is cold, controlling, and thirsts insatiably for power. Sure, Lady McBeth wasn’t exactly a complicated villainess either, but maybe it’s only an issue here because everyone feels so one-note. Marco is no different: perhaps his struggle with his unique brand of PTSD would have made him easy to sympathize with had it not been for the strange decision to have those he confides in take him at his word almost immediately when Marco begins to suspect Raymond of being dangerous. Consider this: he breaks into an innocent man’s home and assaults the hired help. And rather than immediately disown him and recommend psychiatric help, his army buddies all immediately decide to join forces with him and funnel all their energy into taking down an alleged conspiracy with no evidence other than Marco’s word. Also, a late-film decision of Marco's to allow a known murderer to enjoy his honeymoon rather than be apprehended right away leads to the deaths of two innocents and a couple of others before the film is over. So he’s not exactly a sterling example of humanity either, only appearing likable next to the vacuous presence of Raymond Shaw.

I also don’t know how much I buy the film’s big twist. The identity of Raymond’s “American operator” seems pretty obvious from the beginning, but you assume they won’t go there because it would just be too absurd. But if anything I’ve said has taught you anything, you’ll know that this is exactly what they decide to do, and combined with everything else I feel like I’m missing some big piece of subtext: what is the film trying to say with it’s blend of Freudian psychology and paranoid politics? I will say though, it’s a unique, bizarre blend regardless, at times veering into nightmarish. Is there something genius going on below the surface that I don’t see? I’m willing to admit it’s possible, but I find myself having trouble believing it.

On the other hand...

Where the film undeniably succeeds is in its balancing of two seemingly contradictory sides of the Red Scare: while there is indeed a communist conspiracy afoot that manages to brainwash an American soldier into killing off politicians and helping the Reds gain a foothold in our government, it’s worth pointing out that the film’s equivalent of the McCarthys…

*start of spoilers*

…are actually in on that very same conspiracy. They’re spreading fear, paranoia, and panic in order to allow them to convince the people that their first amendment rights must be restricted in order to keep communists from infiltrating America’s institutions, which only gains them a further foothold. Gee, that sounds kind of familiar…

*end of spoilers*

And then there’s the ending, which was undeniably shocking. In fact, all of the violence in this film is kind of shocking, and it’s in these sequences that the film really comes to life. Effective use of dutch angles, extreme closeups, and lots of fake sweat gives the visual texture of the film a desperate intensity appropriate for its themes and narrative. Performances are generally strong - I mean, they can read this dialogue with a straight face for one thing - with Sinatra doing an especially solid job. I won’t mention the frankly embarrassing scene of him brawling with another man if you don’t. Laurence Harvey on the other hand... I just don't know. Some of his line deliveries make me cringe a bit, but that could be more thanks to the writing itself than the performance. It's hard to say.

So yes, go ahead and give it to me. Tell me I’m not a real cineste and tell me that I'm being unfair. I’m totally willing to admit that that could be true, but while you’re at it, could you also help explain to me what it is that I’m missing here? I don’t want to give the impression that I disliked the film: quite the opposite actually, as I’d rather a film shock me with its bizarre choices rather than bore me with its mediocrity or pedestrian aspirations. It’s clear to me that The Manchurian Candidate is an essential film in the development of the political thriller, and that it captures a rich snapshot of an era in America when paranoia and suspicion were through the roof. Unfortunately, a number of strange choices and a general narrative emphasis on exposition and clumsy plotting confuse matters, though in any case, this certainly won’t be my last viewing of the film, which I would consider a success.

Comments

Post a Comment